The Urban Roamer has talked about places, events, and issues. Now, beginning with this entry, the Urban Roamer will be featuring from time to time the people who have helped shaped Metro Manila in this new feature called “Metropolis Builders.” We will be looking at the contributions of urban planners, architects, visual artists, and other visionaries who have helped enrich the metropolitan landscape. And it is apt that the first figure to be featured here is the one who was instrumental in shaping the Manila that we know today…

Born on September 4, 1846 in New York State, Daniel Burnham was as an American architect and urban planner who first came into prominence with his work at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893 to celebrate the 400th anniversary of the expedition of Christopher Columbus to what would eventually be known as the Americas in 1492. Those who attended the fair were in awe of Burnham’s neoclassical design of the expo grounds that is reminiscent of European cities. And it was not an arbitrary choice of design. The event was an avenue for Burnham to first convey his ideas for a model city, in his words a “city beautiful” which would put American cities at par with those in Europe in terms of layout, architecture, and other aspects.

Soon enough, civic organizations and local officials were approaching Burnham to help create for their own cities in accordance with the “City Beautiful” ideal. With such zeal for this ideal and his work ethic, Burnham was able to churn out different master plans for the cities of Chicago, San Francisco, and Washington D.C., Perhaps the most well-known contribution Burnham made in American city planning would be his work in Washington D.C., as he helped conceive what would become the National Mall, the wide open, green space between the Lincoln Memorial and the Capitol Building, with the Washington Monument and the reflective pool in between. (something to note later on in this entry)

It would not be long as well before the American government began to take notice of his work right at the same time that the United States was not only undergoing rapid industrialization but also taking those first steps to become a global power.

BURNHAM’S MANILA PLAN

In the midst of the work he was doing Washington D.C. and other projects, in 1904 the US government tapped Burnham to help draw out the plans for the capital of its newly-acquired colony, Manila in the Philippines, (or the Philippine Islands as it was known at that time) as well as that of a city up north called Baguio, which was decreed by the American colonial government as the official summer capital of the islands. Burnham accepted the job with enthusiasm and a sense of patriotism, all in the name of the motherland. Accompanied by his assistant Pierce Anderson, Burnham arrived in Manila on December 7, 1904 and stayed in the country for almost a month, surveying the two cities and understanding their layout and environment at the time. Back in the US, Burnham then worked on drawing out the plans for Manila and Baguio, a task he completed by June 1905 and was eventually approved by US Congress a year later.

Burnham’s Manila plan drew its influences mainly from his plans for Chicago, San Francisco, and Washington. In fact, they all share some common characteristics like wide radial avenues, landscaped promenades, and, most importantly, a civic core that is envisioned to be the center of the city. In Manila’s case, Burnham placed the civic core right in the area fronting the park we now know as Rizal Park as that area was to be the site of the Philippine Capitol Building. Echoing back to Burnham’s design for Washington’s National Mall, he expropriated that concept in the creation of Manila’s own “national mall” with an open green space between the Philippine Capitol and the yet-to-be-built at that time Rizal Monument and some civic buildings surrounding the mall.

Burnham also conceived a road network radiating from the civic core, making the core the central part of Manila. In addition, he also proposed circumferential roads that will help bring about accessibility. He also conceived the city to have large parks in the different parts of the city and a transport system that is accessible to all. He also emphasized zoning in the city as there were provisions for construction of hospitals, social clubs, a hotel, school center, yacht club, charitable institutions, among others.

While it can be argued that Burnham’s Manila Masterplan aimed to make the city as American as it could be, Burnham took into consideration and actually respected the city’s Hispanic heritage. For instance, he recommended the preservation of Intramuros even though some American authorities thought it was out of place in the city they were trying to create. Burnham also championed Manila’s waterways or esteros as a means of transport comparable to what Venice has with its canals.

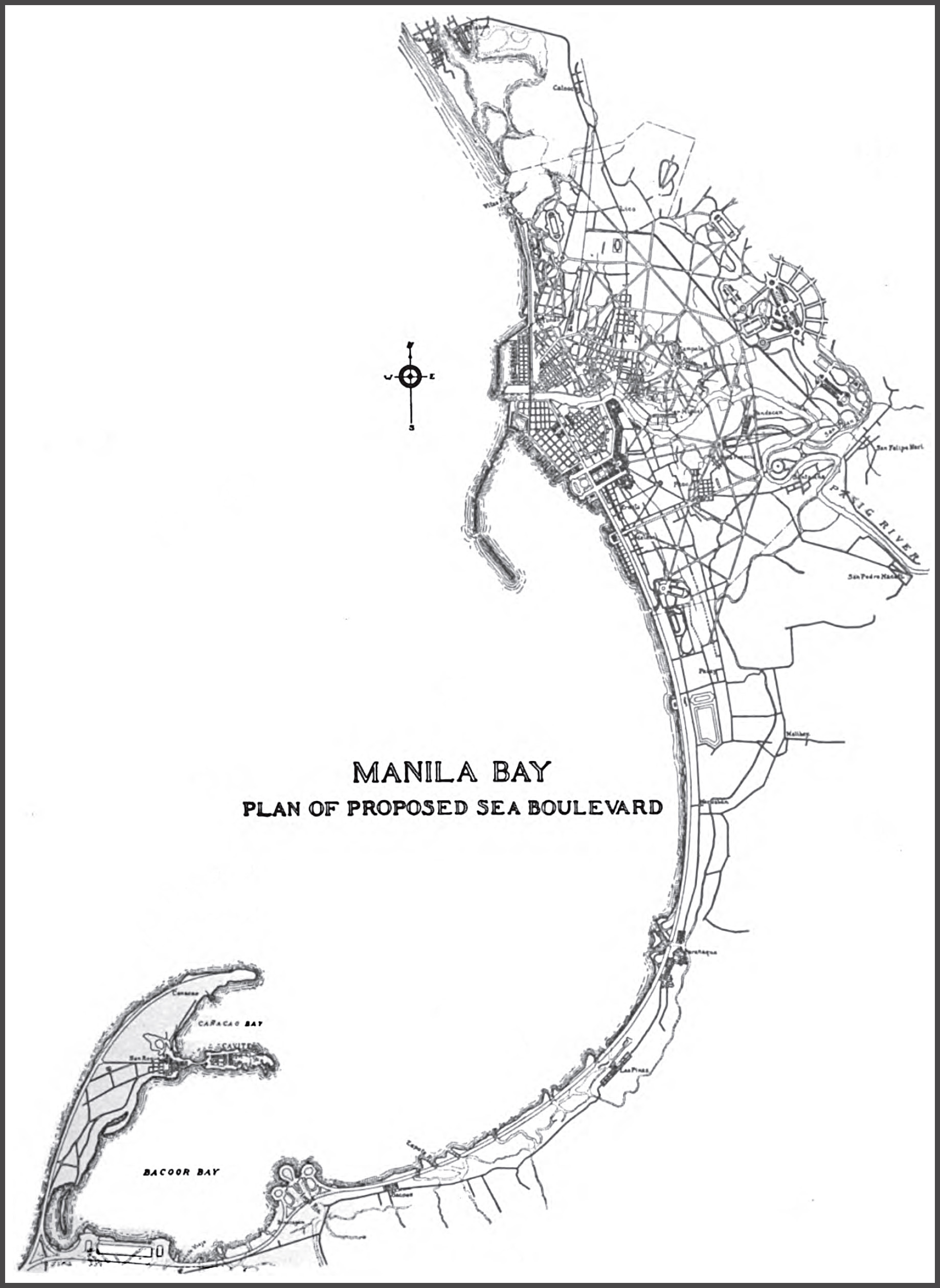

Perhaps the most significant contribution Burnham made in Manila’s development was waterfront development, drawn from his experience in creating the Chicago masterplan which conceived waterfront development along the lake as well as having seen for himself the Manila Bay and the sunset there that many have come to appreciate. For Manila, he conceived that a number of civic structures would be located along the bay, including what would become the Manila Hotel, Army and Navy Club and Elks Club buildings, and the US Embassy. He also conceived a long road network by the bay from Rizal Park all the way to Cavite City, paving the way to what would become the road network that is Roxas Boulevard-Manila-Cavite Coastal Road.

LEGACY

Daniel Burnham died on June 1, 1912 before seeing at least some of his recommendations in his Manila plan would come into fruition. Then again, those plans never got to be fully realized as various factors like funding, the decision to move the capitol complex up north, and World War II hindered them until they were almost forgotten by a city trying to forget the loss and horrors of the past and too eager to move on. Nevertheless, some elements of the Burnham plan remain to this day: the radial road network, the circumferential roads, and the road network by Manila Bay. (though still somewhat incomplete as its length has yet to reach Cavite City as it was originally planned)

At the same time, the rise of “nationalistic fervor” in the years after the war made some people repudiate Burnham as some tool of American imperialism in the country who tried to shove down the “city beautiful” concept into Manila’s throat so that Manila can be made into a model American city that the US can show off to the world. While there may be some truth to this matter, they seem to forget that Burnham also wanted to make Manila a cosmopolitan city that embraces the old and the new and and livable city that is enjoyed by all.

Now with the many problems Manila is facing today brought about by congestion and haphazard planning, among many others, it would not hurt for one to look back at what Daniel Burnham originally wanted Manila to be so we can somehow alleviate, if not totally solve, the city’s current problems. Some of those ideas Burnham have in mind may not be applicable in the current setting, but we can draw inspiration from them so we can create a better, more comprehensive plan that should be implemented for the city’s sake. The Dream Plan of JICA is a good starting point to continue where Burnham left off and finally realize that dream of a city beautiful for Manila.

Acknowledgements as well to Gerard Lico’s book Arkitekturang Pilipino, Wikipedia, and the Inquirer (via Google News)

2 Comments

c. ibarra

I have always thought that Burnham planned old Manila as “little Chicago”. Dewey (Roxas) Boulevard and the high rise buildings across Manila Bay are reminiscent of the landscape along Lake Shore Drive on the gold coast across Lake Michigan. This article affirmed my observation. Thanks for the information.

Convair

I’ve read somewhere online but i’m not sure if its true, that in the late 1930s Pres. Quezon decided that the budget of 16 million pesos used to finish the Burnham plan decided to realign it for “irrigation projects”, which would have been nice actually. In reality the budget was instead used to plan and build his new dream capital named after him. I think this might be true. Quezon really is some kind of a politico in my opinion who once tried to block a Philippine independence bill in the 1930s.